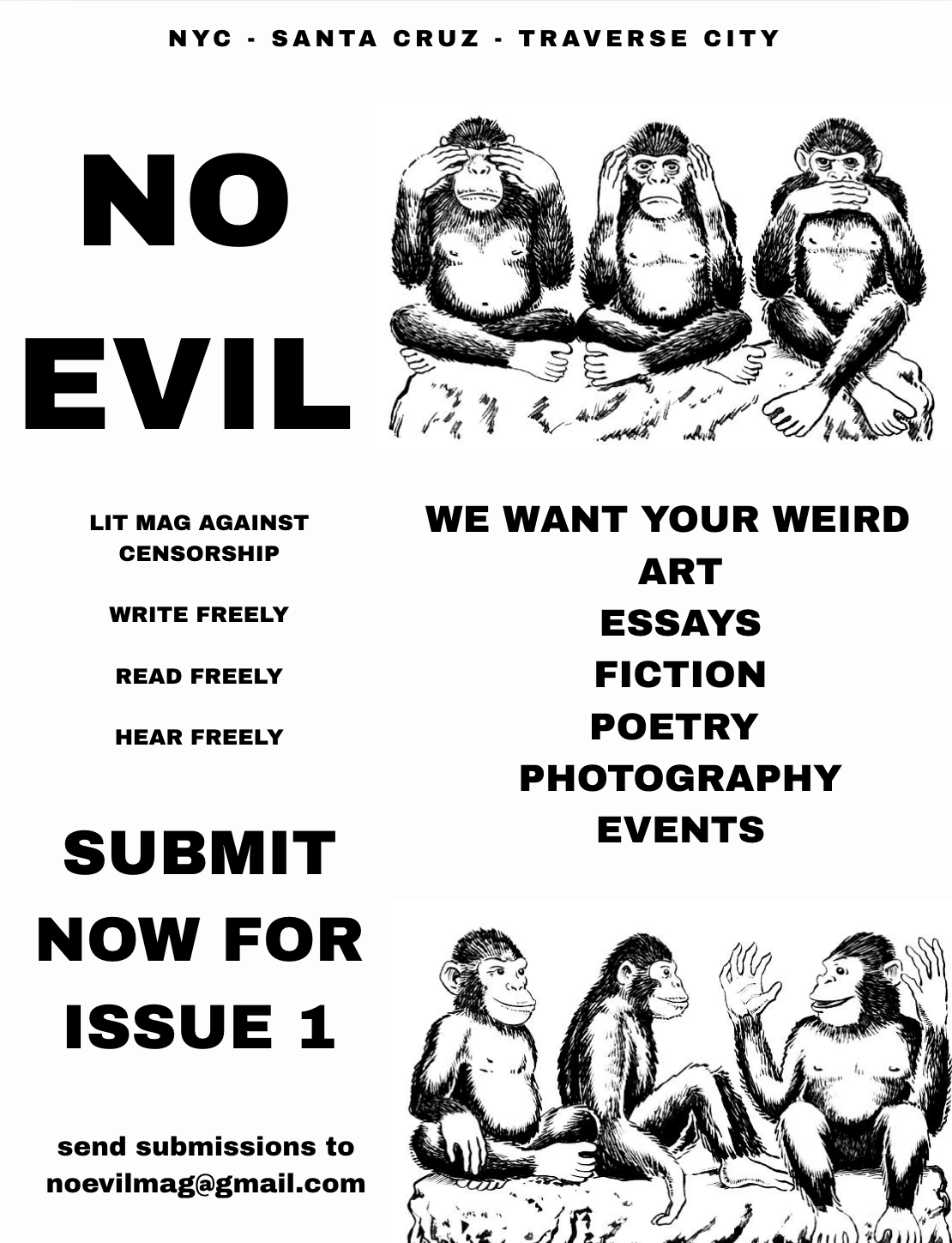

Submit to No Evil! And follow the project at @noevilmag on Instagram!

TITLE HEADING

Title description, Sep 2, 2017

Image

Some text..

Sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco.

About Me

Santa Cruz Youth Poet Laureate '25-'26

IYWS '24

YYGS '25

Contact me

Email: finn.fmaxwell@gmail.com

Instagram: @nnifmax